|

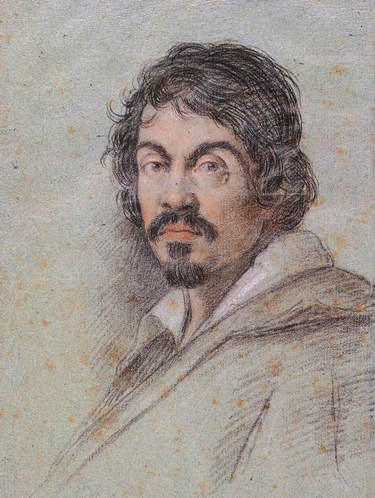

Yes, they exist! At the height of the Roman inquisition in the late sixteenth, early seventeenth centuries, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio ignored the rigid rules that guided what could be painted. Rather than follow the current style based on idealized human beings in ennobling religious stories, he used real people as models. More than that, he invented a genre based on daily life rather than on religious or historical stories. He taught people to see the holy in the everyday and the everyday in the holy. This alone was a tremendous act of rebellion and could have led to imprisonment, even death. Caravaggio did go to prison, many times, but not for the crime of pictorial heresy. His first arrest was for carrying a sword without a permit— yes, you needed a sword license then, much as you need a gun permit today. His second arrest happened when an officer stopped him for carrying a weapon. Though Caravaggio had the permit, he refused to show it. The third time he was spotted carrying his sword, he showed the permit. The officer thanked him, but Caravaggio couldn't resist cursing out the policeman, so he was arrested for insulting an officer. But the best arrest was for assault with a vegetable. This is the official deposition, taken 18 November 1599: It was around five in the afternoon and the aforesaid Caravaggio, along with some others, was eating in the Moor of the Magdalene where I work as a waiter. I brought him eight cooked artichokes, that is four in butter and four in oil and he asked me which were cooked in oil and which in butter. I told him that he could smell them and easily know which were cooked in butter and which were cooked in oil, and he got up in a fury and without saying a word, he took the plate from me and threw it in my face where it hit my cheek. You can still see the wound. And then he reached for his sword and he would have hit me with it, but I ran away and came right to this office to present my complaint. Caravaggio went on to be arrested many more times for more serious assaults, including murder. Now, though, he's not remembered as a criminal, but rather as an artistic genius who inspired generations of followers. Judith Beheading Holofernes (1599–1602) is the first of several paintings in which Caravaggio chose to depict the dramatic and gory subject of decapitation. Wikimedia Basket of Fruit, c. 1595–1596, oil on canvas. Caravaggio's realistic view of things is exemplified in this still life. The bowl is teetering on the edge of the table, some of the leaves are withered, and the apple in the front is far from perfect. Wikimedia  Marissa Moss's book Caravaggio:Painter on the Run tells a compelling story that humanizes Caravaggio while describing the political and social atmosphere in which he lived. Moss, Marissa. "Police Reports from the Sixteenth Century?" Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 24 01 2018, http://www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/police-reports-from-the-sixteenth-century6158812.

0 Comments

Diego Velázquez, "Portrait of Juan de Pareja," 1650,Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 69.9 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, USA Diego Velázquez, "Portrait of Juan de Pareja," 1650,Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 69.9 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, USA Diego Velazquez (1599 – 1660) was a famous Spanish painter. He had a slave named Juan de Pareja (1606 – 1670). Call him an indentured servant if you want, but it’s more accurate to say he was Velazquez's slave, as he was not at liberty to leave. For years, Pareja prepared brushes, ground pigments, and stretched canvasses for the artist. While he was at it, Pareja observed his master carefully, and secretly taught himself how to use the materials, and how to paint. Pareja was referred to as a Morisco in Spanish. One way to translate the word is that he had mixed parentage (the offspring of a European Spaniard and a person of African descent). Another way to translate the word is that he was a Moor—someone descended from Muslims who had remained in Spain after its conquest by Ferdinand and Isabella. In 1650, Velazquez was preparing to paint a portrait of Pope Innocent X. As practice, he painted Pareja, who had accompanied the artist to Italy. Here is the portrait. It's a pretty amazing picture, isn't it? Velazquez got all sorts of praise for it from the artists in Rome—he was even elected into the Academy of St. Luke. According to some sources, Velazquez would not allow Pareja to pick up a paintbrush. But one day, when King Philip IV was due to visit Velazquez, Pareja placed one of his own paintings where the king would see it. When the king admired it, believing it to be by Velazquez, Pareja threw himself at the king’s feet and begged for the King to intercede for him. Whether or not that story is true, Pareja did become an accomplished painter, and impressed the king so much that he ordered Pareja freed. Pareja remained with the Velazquez family until his death. It was hard to find examples of his paintings, but here are two that are attributed to him.  Sarah Albee's latest book is Poison: Deadly Deeds, Perilous Professions and Murderous Medicines. You can read a review that gives you a dose of what's in this book. MLA 8 Citation Albee, Sarah. "The Painter Was a Slave." Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 25 Oct. 2017, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/the-painter-was-a-slave.  Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571 – 1610) came from humble origins, the son of a stonecutter. He moved from Milan to Rome while in his twenties, looking for painting commissions in the newly built churches and palazzi that were springing up there. Caravaggio became known as a master of realism—populating his paintings with contemporary, ordinary people—many of them rogues and ruffians from the mean streets of Rome. People were shocked by his realistic paintings. They were used to looking at devotional paintings showing choirs of angels and golden shafts of light beaming down from heaven. A big part of Caravaggio’s problem is that he felt (correctly) that he was underappreciated as a painter. He was hot-headed and quick to pick a fight, and kept getting into trouble. In 1594 he was arrested for hurling a plate of artichokes at a waiter, and he was forever getting involved in Roman street brawls. In 1606 he really messed up. While he was playing an early version of tennis, palla a corda, with a close friend, a wealthy acquaintance named Ranuccio Tomassoni walked by with a couple of his relatives and challenged Caravaggio to a game. They played. Each thought he’d won. They drew swords. They chased each other around, hacking away. Caravaggio was slashed twice, but then buried his blade in his enemy’s stomach. Ranuccio died shortly thereafter, and Caravaggio’s friends dragged Caravaggio away to a nearby house to bandage him up. The police came after him, and Caravaggio fled for the hills outside of Rome. He became a fugitive from the law. He was convicted of murder in absentia, and sentenced to death. For the next few years, he continued to paint while on the run. His reputation as an artist was growing. Still pursued by the law, he fled to Malta in 1607, got in trouble there, and fled to Sicily. By 1609, he was widely known as a master painter, and he traveled to Naples to await word from the Pope that his petition to be pardoned might be approved. While there, he was ambushed by four assassins, who stabbed him around the face and neck. He managed to survive the attack, but was left disfigured. When his papal pardon finally arrived, in 1610, he set sail for Rome but fell ill on the way with a fever—probably malaria. He died in 1610.  Sara Albee's latest book is Poison: Deadly Deeds, Perilous Professions, and Murderous Medicines. , Vicki Cobb reviewed this fascinating book-- poisons are in more places than you can ever imagine. Get A Dose Of This! MLA 8 Citation

Albee, Sarah. "Renaissance Bad Boy." Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 5 Jan. 2018, www.nonfictionminute.org/Renaissance-Bad-Boy. |

*NEWS

|

For Vicki Cobb's BLOG (nonfiction book reviews, info on education, more), click here: Vicki's Blog

The NCSS-CBC Notable Social Studies Committee is pleased to inform you

that 30 People Who Changed the World has been selected for Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People 2018, a cooperative project of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) & the Children’s Book Council

Categories

All

Abolitionists

Adams Janus

Adaptation

Adaptations

Adkins Jan

Advertising

Aerodynamics

Africa

African American History

African Americans

Africa West

Agriculture

Aircraft

Air Pilots

Air Pressure

Air Travel

Albee Sarah

Alchemy

Alligators

Allusion

American History

American Icons

Amphibians

Amundsen Roald

Anatomy

Ancient

Ancient Cultures

Anderson Marian 1897-1993

Animal Behavior

Animal Experimentation

Animal Intelligence

Animals

Animation

Antarctica

Ants

Apache Indians

Apes

April Fool's Day

Architecture

Argument

Arithmetic

Art

Art Deco

Artists

Arts

Asia

Astronauts

Astronomy

Athletes

Atomic Theory

Audubon Societies

Authors

Autobiography

Automobiles

Aviation

Awards

Bacteria

Baseball

Battuta Ibn

Bears

Beatles

Beavers

Bees

Biodegradation

Biography

Biology

Biomes

Biomimicry

Biplanes

Birds

Black Death

Black History

Blindness

Blizzards

Bombs

Bonaparte Napoleon

Boone Daniel

Botany

Brazil

Bridges

Brill Marlene Targ

Brooklyn Bridge

Brown John

Buffaloes

Building Materials

Butterflies

Caesar

Caesar Julius

Caissons

Calculus

Calendars

Cannibal

Capitals

Caravaggio

Carbon Dioxide

Carnivores

Carson Mary Kay

Cartoons & Comics

Carving (Decorative Arts)

Cascade Range

Castaldo Nancy

Castles

Castrovilla Selene

Cathedrals

Cats

Caves

Celts

Cemeteries

Chemistry

Children's Authors

Child Welfare

China

Choctaw Indians

Christmas

Chronometers

Cicadas

Cinco De Mayo

Ciphers

Circle

Citizenship

Civil Rights

Civil Rights Movements

Civil War

Civil War - US

Climate

Climate Change

Clocks And Watches

Clouds

Cobb Vicki

COBOL (Computer Language)

Code And Cipher Stories

Collard III Sneed B.

Collectors And Collecting

Color

Commerce

Communication

Competition

Compilers

Composers

Computers

Congressional Gold Medal

Consitution

Contests

Contraltos

Coolidge Calvin

Cooling

Corms

Corn

Counterfeiters

Covid-19

Crocodiles

Cryptography

Culture

Darwin Charles

Declaration Of Independence

Decomposition

Decompression Sickness

Deep-sea Animals

Deer

De Medici Catherine

Design

Detectives

Dickens Charles

Disasters

Discrimination

Diseases

Disney Walt

DNA

Dogs

Dollar

Dolphins

Douglass Frederick 1818-1895

Droughts

Dr. Suess

Dunphy Madeleine

Ear

Earth

Earthquakes

Ecology

Economics

Ecosystem

Edison Thomas A

Education

Egypt

Eiffel-gustave-18321923

Eiffel-tower

Einstein-albert

Elephants

Elk

Emancipationproclamation

Endangered Species

Endangered-species

Energy

Engineering

England

Englishlanguage-arts

Entomology

Environmental-protection

Environmental-science

Equinox

Erie-canal

Etymology

Europe

European-history

Evolution

Experiments

Explorers

Explosions

Exports

Extinction

Extinction-biology

Eye

Fairs

Fawkes-guy

Federalgovernment

Film

Fires

Fishes

Flight

Floods

Flowers

Flute

Food

Food-chains

Foodpreservation

Foodsupply

Food-supply

Football

Forceandenergy

Force-and-energy

Forensicscienceandmedicine

Forensic Science And Medicine

Fossils

Foundlings

France

Francoprussian-war

Freedom

Freedomofspeech

French-revolution

Friction

Frogs

Frontier

Frontier-and-pioneer-life

Frozenfoods

Fugitiveslaves

Fultonrobert

Galapagos-islands

Galleys

Gametheory

Gaudi-antoni-18521926

Gender

Generals

Genes

Genetics

Geography

Geology

Geometry

Geysers

Ghosts

Giraffe

Glaciers

Glaucoma

Gliders-aeronautics

Global-warming

Gods-goddesses

Gold-mines-and-mining

Government

Grant-ulysses-s

Grasshoppers

Gravity

Great-britain

Great-depression

Greece

Greek-letters

Greenberg Jan

Hair

Halloween

Handel-george-frederic

Harness Cheryl

Harrison-john-16931776

Health-wellness

Hearing

Hearing-aids

Hearst-william-randolph

Henry-iv-king-of-england

Herbivores

Hip Hop

History

History-19th-century

History-france

History-world

Hitler-adolph

Hoaxes

Holidays

Hollihan Kerrie Logan

Homestead-law

Hopper-grace

Horses

Hot Air Balloons

Hot-air-balloons

Housing

Huguenots

Human Body

Hurricanes

Ice

Icebergs

Illustration

Imagery

Imhotep

Imperialism

Indian-code-talkers

Indonesia

Industrialization

Industrial-revolution

Inquisition

Insects

Insulation

Intelligence

Interstatecommerce

Interviewing

Inventions

Inventors

Irrational-numbers

Irrigation

Islands

Jacksonandrew

Jazz

Jeffersonthomas

Jefferson-thomas

Jemisonmae

Jenkins-steve

Jet-stream

Johnsonlyndonb

Jokes

Journalism

Keeling-charles-d

Kennedyjohnf

Kenya

Kidnapping

Kingmartinlutherjr19291968

Kingmartinlutherjr19291968d6528702d6

Kings-and-rulers

Kings Queens

Kings-queens

Koala

Labor

Labor Policy

Lafayette Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert Du Motier Marquis De 17571834

Landscapes

Languages-and-culture

Law-enforcement

Layfayette

Levers

Levinson Cynthia

Lewis And Clark Expedition (1804-1806)

Lewis Edmonia

Liberty

Lift (Aerodynamics)

Light

Lindbergh Charles

Liszt Franz

Literary Devices

Literature

Lizards

Longitude

Louis XIV King Of France

Lumber

Lunar Calendar

Lynching

Macaws

Madison-dolley

Madison-james

Madison-james

Mammals

Maneta-norman

Maneta-norman

Marathon-greece

Marine-biology

Marine-biology

Marines

Marsupials

Martial-arts

Marx-trish

Mass

Massachusetts-maritime-academy

Mass-media

Mastodons

Mathematics

May-day

Mcclafferty-carla-killough

Mcclafferty-carla-killough

Mckinley-william

Measurement

Mechanics

Media-literacy

Media-literacy

Medicine

Memoir

Memorial-day

Metaphor

Meteorology

Mexico

Mickey-mouse

Microscopy

Middle-west

Migration

Military

Miners

Mississippi

Molasses

Monarchy

Monsters

Montgomery

Montgomery-bus-boycott-19551956

Montgomery-heather-l

Monuments

Moon

Moran-thomas

Morsecode

Morsesamuel

Moss-marissa

Moss-marissa

Motion

Motion-pictures

Mummies

Munro-roxie

Munro-roxie

Musclestrength

Museums

Music

Muslims

Mythologygreek

Nanofibers

Nanotechnology

Nathan-amy

Nathan-amy

Nationalfootballleague

Nationalparksandreserves

Nativeamericans

Native-americans

Native-americans

Naturalhistory

Naturalists

Nature

Nauticalcharts

Nauticalinstruments

Navajoindians

Navigation

Navy

Ncaafootball

Nervoussystem

Newdeal19331939

Newman-aline

Newman-aline

Newton-isaac

New-york-city

Nobelprizewinners

Nomads

Nonfictionnarrative

Nutrition

Nylon

Nymphs-insects

Oaths Of Office

Occupations

Ocean

Ocean-liners

Olympics

Omnivores

Optics

Origami

Origin

Orphans

Ottomanempire

Painters

Painting

Paleontology

Pandemic

Paper-airplanes

Parksrosa19132005

Parrots

Passiveresistance

Patent Dorothy Hinshaw

Peerreview

Penguins

Persistence

Personalnarrative

Personification

Pets

Photography

Physics

Pi

Pigeons

Pilots

Pinkertonallan

Pirates

Plague

Plains

Plainsindians

Planets

Plantbreeding

Plants

Plastics

Poaching

Poetry

Poisons

Poland

Police

Political-parties

Pollen

Pollution

Polo-marco

Populism

Portraits

Predation

Predators

Presidentialmedaloffreedom

Presidents

Prey

Prey-predators

Prey-predators

Prime-meridian

Pringle Laurence

Prohibition

Proteins

Protestandsocialmovements

Protestants

Protestsongs

Punishment

Pyramids

Questioning

Radio

Railroad

Rainforests

Rappaport-doreen

Ratio

Reading

Realism

Recipes

Recycling

Refrigerators

Reich-susanna

Religion

Renaissance

Reproduction

Reptiles

Reservoirs

Rheumatoidarthritis

Rhythm-and-blues-music

Rice

Rivers

Roaringtwenties

Roosevelteleanor

Rooseveltfranklind

Roosevelt-franklin-d

Roosevelt-theodore

Running

Russia

Safety

Sanitation

Schwartz David M

Science

Scientificmethod

Scientists

Scottrobert

Sculpture

Sculpturegardens

Sea-level

Seals

Seals-animals

Secretariesofstate

Secretservice

Seeds

Segregation

Segregationineducation

Sensessensation

September11terroristattacks2001

Seuss

Sextant

Shackletonernest

Shawneeindians

Ships

Shortstories

Silkworms

Simple-machines

Singers

Siy Alexandra

Slavery

Smuggling

Snakes

Socialchange

Social-change

Socialjustice

Social-justice

Socialstudies

Social-studies

Social-studies

Sodhouses

Solarsystem

Sound

Southeast-asia

Soybean

Space Travelers

Spain

Speech

Speed

Spiders

Spies

Spiritualssongs

Sports

Sports-history

Sports-science

Spring

Squirrels

Statue-of-liberty

STEM

Storms

Strategy

Sugar

Sumatra

Summer

Superbowl

Surgery

Survival

Swanson-jennifer

Swinburne Stephen R.

Synthetic-drugs

Taiwan

Tardigrada

Tasmania

Tasmanian Devil

Tasmanian-devil

Technology

Tecumsehshawneechief

Telegraph-wireless

Temperature

Tennis

Terrorism

Thomas Peggy

Thompson Laurie Ann

Time

Titanic

Tombs

Tortoises

Towle Sarah

Transcontinental-flights

Transportation

Travel

Trees

Trung Sisters Rebellion

Tundra

Turnips

Turtles

Typhoons

Underground Railroad

Us-environmental-protection-agency

Us History

Us-history

Ushistoryrevolution

Us History Revolution

Us-history-war-of-1812

Us Presidents

Ussupremecourtlandmarkcases

Vacations

Vaccines

Vangoghvincent

Vegetables

Venom

Vietnam

Viruses

Visual-literacy

Volcanoes

Voting-rghts

War

Warne-kate

Warren Andrea

Washington-dc

Washington George

Water

Water-currents

Wax-figures

Weapons

Weather

Weatherford Carole Boston

Whiting Jim

Wildfires

Winds

Windsor-castle

Wolves

Woman In History

Women

Women Airforce Service Pilots

Women-airforce-service-pilots

Womeninhistory

Women In History

Women-in-science

Women's History

Womens-roles-through-history

Wonder

Woodson-carter-godwin-18751950

World-war-i

World War Ii

World-war-ii

Wright Brothers

Writing

Writing-skills

Wwi

Xrays

Yellowstone-national-park

Zaunders Bo

ArchivesMarch 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

September 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

March 2017

The NONFICTION MINUTE, Authors on Call, and. the iNK Books & Media Store are divisions of iNK THINK TANK INC.

a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit corporation. To return to the iNK Think Tank landing page click the icon or the link below. :

http://inkthinktank.org/

For more information or support, contact thoughts@inkthinktank.org

For Privacy Policy, go to

Privacy Policy

© COPYRIGHT the Nonfiction Minute 2020.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This site uses cookies to personalize your experience, analyze site usage, and offer tailored promotions. www.youronlinechoices.eu

Remind me later

Archives

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

October 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

December 2018

September 2018

June 2018

May 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed