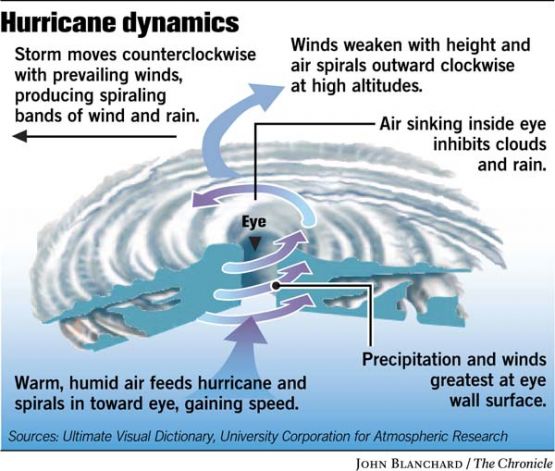

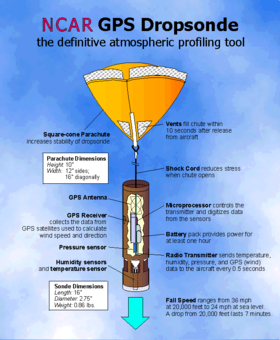

Dr. Hugh Willoughby, of Florida International University, was one of the first meteorologists to ever fly into the eye of a hurricane. Now the job is done by the Hurricane Hunters—a team of pilots, navigators and meteorologists who fly into these dangerous storms to help keep us safe. Here’s what I learned when I interviewed Hugh Willoughby: What is a hurricane eye? Hurricanes are circular storms so the wind blows around in a circle. The eye is the center of a hurricane. If a circular storm doesn’t have an eye, it is not a hurricane—it’s a tropical storm. The eye is surrounded by a ring of clouds called the eyewall. Within the eye, there is a calm area that is cloudless all the way up to space. The winds are strongest just at the inner edge of the eyewall, which is composed of violent thunderstorms with strong updrafts and downdrafts. The hurricane pinwheels out from the eyewall as spiral bands of wind and rain, which stretch for miles. When a hurricane’s eye passes over land, the storm suddenly stops and the sun comes out. But the relief is short-lived as the other side of the storm soon slams into the area. How do Hurricane Hunters help us? Hurricane Hunters fly into the eye of hurricanes that are heading towards our shores to help predict where the storm will make landfall. On every mission they must find the center of the storm at least twice and at most four times over a period of several hours because the change in position of the center of the eye tells us the direction the storm is moving and how fast it is moving. They also drop packages called dropsondes that contain measuring instruments for air pressure, humidity, and wind speed at the eyewall. These measurements tell us the destructive power of the storm or its “category.” During a hurricane season (from June 1 to November 30) the Hurricane Hunters and their fleet of ten airplanes can get data on three storms, twice a day. So flying into a hurricane’s eye is pretty routine for them. Is it dangerous? The planes can easily handle changes in air pressure and wind speeds that create “bumps” and it can be pretty bumpy going through the eyewall. But, in more than sixty years there have been only four accidents. All on board agree that the view of the eyewall from inside the eye is worth it! The plane has transported them inside nature’s most magnificent amphitheater. (c) Vicki Cobb 2014 Harvey and Irma have alerted everyone to the dangers of a hurricane. We can predict the course of a hurricane by flying into a hurricane and repeatedly measuring wind speed, humidity, air pressure, and temperature. Here's a video that will give you a taste of what it looks like as you approach an eye wall. It is filmed from a plane penetrating Hurricane Katrina.

MLA 8 Citation Cobb, Vicki. "Flying into the Eye of a Storm." Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 18 Sept. 2017, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/ flying-into-the-eye-of-a-storm.

2 Comments

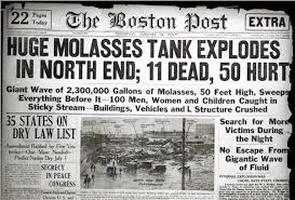

Most disasters are a cascade: small failures and minor circumstances, one leading to another, blossom into a cataclysm. On January 16, 1919, a cascade of tremendous size was poised above Boston’s North End. The weather was one factor: unusually warm for winter. Purity Distilling Company fermented and distilled molasses to make rum and alcohol. The 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, prohibiting sales of alcoholic beverages, was due to be passed the very next day. This may have prompted Purity to collect as much molasses as possible. The enormous tank holding the molasses was about 50 feet tall and 90 feet in diameter, holding 2,300,000 gallons. It was poorly built of thin steel painted brown to hide its leaks. Local families often collected some of the dripping molasses to sweeten their food. The unseasonably warm temperature quickly rose from 2° F (-16.7° C) to 40° F (4.4° C), expanding the liquid, and natural fermentation produced CO2 increasing tank pressure. Just after noon, North End families felt the ground shake and heard a sound like a machine gun— the tank’s rivets popping out. The big tank exploded, sending a 25-foot wall of molasses roaring down the hill toward Commercial Street at about 35 miles an hour. In front of the molasses went a blast of air that blew some folks off their porches and tumbled others along the street like rag dolls. Homes and buildings were destroyed, smashed from their foundations. Horses pulling wagons were swept away. The steel girders of the Boston Elevated Railway were buckled, knocking a rail-car off the tracks. Twenty-one people were killed and more than a hundred were injured. Many were saved by Massachusetts Maritime Academy cadets who rushed off their docked training vessel and plunged into the brown goo to rescue people. It’s difficult to know how many dogs, cats and horses died. As you can imagine, the clean-up was awful. Firehoses from hydrants and harbor fireboats washed away as much as possible. Boston Harbor was brown for months. Sightseers tracked the goo back to homes, into hotels, onto pay-phones and onto doorknobs. Everything Bostonians touched was sticky for months. Some say that on a hot summer day along the North End’s docks, the sickly sweet smell of molasses lingers. Bostonians can smile at the Great Molasses Flood now, but in January of 1919, that cascade of disasters was deadly serious. Jan Adkins is an author, an illustrator, and a superb storyteller. Read about him on his Amazon page. He is also a member of iNK's Authors on Call and is available for classroom programs through Field Trip Zoom, a terrific technology that requires only a computer, wifi, and a webcam. Click here to find out more. MLA 8 Citation

Adkins, Jan. "The Great Boston Molasses Flood: How Can a Tragedy Sound Funny?" Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 19 Jan. 2018, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/ The-Great-Boston-Molasses-Flood-How-Can-a-Tragedy-Sound-Funny?  Early in 1980, Mt. St. Helens in southwestern Washington state began showing signs that it was about to erupt. Part of the state’s Cascade Range, the mountain was an active volcano that had been dormant for 123 years. The possibility of seeing the “fireworks” prompted many people to head for the mountain. The sightseers included Ron and Barbara Seibold and their two children, who parked about 12 miles north of the mountain. That was well beyond two danger zones that scientists had established. En route to the mountain, the children—Kevin, aged 7, and his 9-year-old sister Michelle—made a cassette tape. They asked questions and the parents answered. “They were goofing around—asking whether or not they would see lava coming out of the mountain,” said a state emergency management official. “One asked if it was dangerous, and both parents cheerfully reassured their kids that they’d be safe.” They weren’t. Exploding on May 18 with a fury far beyond what scientists had expected, the blast generated the largest landslide in U.S. history and flattened millions of trees. Uncounted tons of ash rose as high as 15 miles into the atmosphere. The Seibolds never had a chance. Ash almost instantly buried their vehicle. They suffocated. The eruption claimed 53 more people, making it the deadliest-ever on the US mainland. One was Harry Truman, who had run the inn at nearby Spirit Lake for more than 50 years. Truman had become somewhat of a folk hero for his refusal to move despite the danger. Twenty-year-old newlyweds Christy and John Killian were camping nine miles from the volcano. Christy died of massive head injuries, her arm around her pet poodle. John and the couple’s retriever were never found. Terry Crall and Karen Varner, both 21, died when a tree fell onto their tent, 14 miles away. Four people outside the tent were unharmed. So were researchers Keith and Dorothy Stoffel, flying a small airplane less than 1,300 feet above the summit at the moment of the eruption. A cloud laced with lightning bolts billowed toward them. They managed to outrun it. Today, much of the vegetation destroyed by the blast has returned. But the mountain—once compared in its graceful contours to Mt. Fuji in Japan—lost 1,300 feet of its height. Its former symmetrical cone shape is now topped by a horseshoe-shaped crater which stands as a mute reminder of the catastrophic eruption.  The top of Mount St. Helens two years after the eruption. The removal of the north side of the mountain reduced St. Helens' height by about 1,300 feet and left a crater 1 mile to 2 miles wide and a half mile deep. The eruption killed 57 people, nearly 7,000 big game animals (deer, elk, and bear), and an estimated 12 million fish from a hatchery. It destroyed or extensively damaged more than 200 homes, 185 miles of highway, and 15 miles of railways.  Volcanoes have been erupting for all of recorded history. More than 3,500 years ago, people on the Greek island of Calliste had a very good life. There was only one problem: Calliste was actually a volcano. Around 1650 BCE, the volcano erupted, blowing out the center of the island and creating a large bay. What was left of Calliste was buried under a thick layer of volcanic ash. Though the island was deserted for many years, people eventually returned. Several centuries ago, it was renamed Santorini. The island has reclaimed its beauty and allure, but the volcano below continues to reshape this little plot of land in the Mediterranean Sea. For more information on Jim Whiting's book on the Santorini eruption, click here. MLA 8 Citation

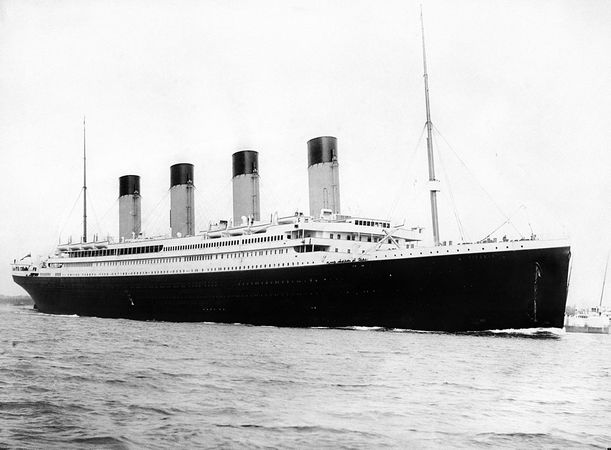

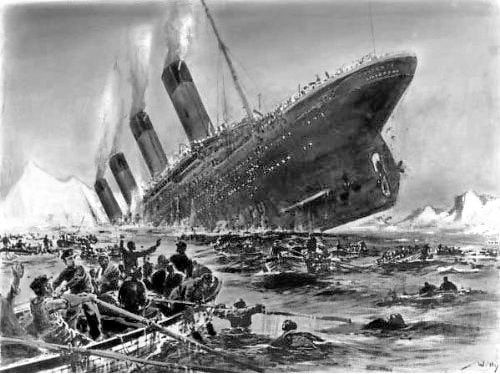

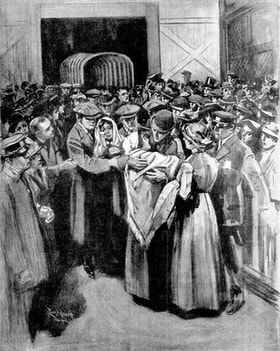

Whiting, Jim. "The Deadly Eruption of Mount St. Helens." Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 5 June 2018, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/ The-Deadly-Eruption-of-Mount-St-Helens.  In the early morning of April 15, 1912, the ocean liner Titanic sank on her maiden voyage after hitting an iceberg. The ship carried just over 2,200 people. More than 1,500 perished. The main reason for the high death toll was that the ship had only 20 lifeboats. As they pulled away from the sinking ship, many were only half-full or even less. Even if all had been filled to capacity, only half the people would have been saved. Why didn’t Titanic carry enough lifeboats for everyone on board? There were several reasons. Titanic’s original design called for 64 lifeboats. That number was later cut in half, then nearly halved again. The ship’s owners felt that too many lifeboats would clutter the deck and obscure the First Class passengers’ views. The ship sailed under safety regulations that originated nearly 20 years earlier, when the largest passenger ships weighed 10,000 tons. Titanic was more than four times that amount. Yet officials maintained that ships had become much safer. Revising the regulations was therefore unnecessary. Under those regulations, Titanic actually had four more lifeboats than she was obligated to carry. Nearly every other vessel of that era was similarly deficient in the quantity of lifeboats. The prevailing thinking at that time was that the ship itself would serve as a gigantic lifeboat. Nearly everyone believed that even a heavily damaged vessel would remain afloat for many hours before sinking. That would allow plenty of time for the lifeboats to go back and forth several times, ferrying passengers to nearby ships. This assumption was not unreasonable. When the smaller liner Republic was involved in a collision in 1909, she remained afloat for more than 24 hours. All 742 passengers and crew were ferried to safety. The flaw with this assumption was that Titanic sank far more rapidly than anyone anticipated. The first rescue ship arrived more than two hours after Titanic had gone down. In 2012 an explosive document emerged. It consisted of safety inspector Maurice Clarke’s handwritten notes, urging the addition of 10 more lifeboats five hours before the ship sailed. The ship’s owners wanted to leave on time. Clarke was threatened with being fired unless he kept his mouth shut. If the owners had followed his advice, almost 700 more people might have survived. The disaster prompted a massive overhaul of regulations. All ships were required to carry enough lifeboats for everyone.  Frederick Douglass was a slave, but from an early age, he was determined to become a free man. He escaped to the North when he was about 20. A few years later, he discovered that he was an outstanding public speaker. For the rest of his life, Frederick would courageously speak out about the issues that affected his fellow blacks. Sometimes his actions placed him in great danger. During his lifetime no other African American did as much for blacks as Frederick Douglass. Even today his memory continues to inspire many people to work for civil rights and racial justice. For more information on Jim Whiting's book, click here. MLA 8 Citation

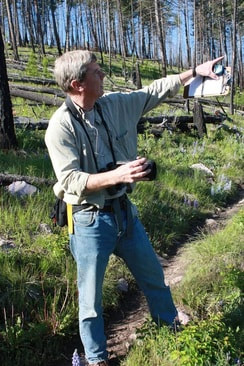

Whiting, Jim. "Titanic - Not Enough Lifeboats." Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 31 May 2018, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/ Titanic-Not-Enough-Lifeboats.   Only you can prevent forest fires! At least that’s what Smokey Bear taught me growing up. His message? All forest fires are bad, and we’re helping nature by putting them all out. Recently, I met a scientist who’s made me rethink this negative message about natural wildfires. His name is Dick Hutto and he’s a biology professor at the University of Montana. “There are two kinds of fires,” Dick explains. “The ones that burn down your house or kill your neighbor are bad, bad, bad. The other ones can be the greatest things in the world.” To prove his point, Dick took me to the Black Mountain burn area, near my home in Missoula, Montana. A severe forest fire burned through this area only ten years ago, and thousands of blackened trees still stand like sentries across the landscape. Surprisingly, this charred landscape explodes with life. Tens of thousands of new tree saplings reach for the sky. Elk and deer graze on the fresh grass growing in the newly-opened areas. More than anything, the songs of birds fill the burned forest. In his research, in fact, Dick discovered that dozens of bird species love fresh burn areas. In the West, 15 bird species prefer burned forests to all other habitats! Woodpeckers pave the way. As soon as a forest burns, legions of wood-boring beetles descend on the forest and lay their eggs in the dead trees. Three-toed, Hairy, and Black-backed Woodpeckers follow and begin devouring the newly-hatched beetle grubs. They also chisel out their own nest holes—holes that are used by Mountain Bluebirds, American Robins, Black-capped Chickadees, and many other species. Because of burned forests, these birds find food and shelter. They also find safety. How? Green forests abound with squirrels and chipmunks—animals that feast on bird eggs. A severe forest fire, though, clears out the small mammals. That means that birds can raise their young much more safely. But listen, don’t take my word for it—or even Dick Hutto’s. To learn more about the benefits of fire, throw a water bottle, lunch, a bird guide, and a pair of binoculars in your backpack and go visit a burn area for yourself. You will be astonished by what you see. Take a notebook or a camera along, too. Part of the fun of discovering our planet is sharing what you see. By doing so you’ll help others realize the importance of natural wildfires and burned forest—and help create a healthier, more interesting world.  Sneed Collard III has written a book about the birds that thrive in burn areas. Fire Birds shows how dozens of bird species not only survive, but actually thrive in burned areas, depending on burns to create a unique and essential habitat that cannot be generated any other way. If you would like more information, click here to go to Sneed's website. If you click the Study Guide tab, you will find a guide that's been prepared for this book. MLA 8 Citation Collard, Sneed B., III. Weblog post. Nonfiction Minute, iNK Think Tank, 11 Oct. 2017, www.nonfictionminute.org/the-nonfiction-minute/rethinking-smokey-bears-message. |

*NEWS

|

For Vicki Cobb's BLOG (nonfiction book reviews, info on education, more), click here: Vicki's Blog

The NCSS-CBC Notable Social Studies Committee is pleased to inform you

that 30 People Who Changed the World has been selected for Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People 2018, a cooperative project of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) & the Children’s Book Council

Categories

All

Abolitionists

Adams Janus

Adaptation

Adaptations

Adkins Jan

Advertising

Aerodynamics

Africa

African American History

African Americans

Africa West

Agriculture

Aircraft

Air Pilots

Air Pressure

Air Travel

Albee Sarah

Alchemy

Alligators

Allusion

American History

American Icons

Amphibians

Amundsen Roald

Anatomy

Ancient

Ancient Cultures

Anderson Marian 1897-1993

Animal Behavior

Animal Experimentation

Animal Intelligence

Animals

Animation

Antarctica

Ants

Apache Indians

Apes

April Fool's Day

Architecture

Argument

Arithmetic

Art

Art Deco

Artists

Arts

Asia

Astronauts

Astronomy

Athletes

Atomic Theory

Audubon Societies

Authors

Autobiography

Automobiles

Aviation

Awards

Bacteria

Baseball

Battuta Ibn

Bears

Beatles

Beavers

Bees

Biodegradation

Biography

Biology

Biomes

Biomimicry

Biplanes

Birds

Black Death

Black History

Blindness

Blizzards

Bombs

Bonaparte Napoleon

Boone Daniel

Botany

Brazil

Bridges

Brill Marlene Targ

Brooklyn Bridge

Brown John

Buffaloes

Building Materials

Butterflies

Caesar

Caesar Julius

Caissons

Calculus

Calendars

Cannibal

Capitals

Caravaggio

Carbon Dioxide

Carnivores

Carson Mary Kay

Cartoons & Comics

Carving (Decorative Arts)

Cascade Range

Castaldo Nancy

Castles

Castrovilla Selene

Cathedrals

Cats

Caves

Celts

Cemeteries

Chemistry

Children's Authors

Child Welfare

China

Choctaw Indians

Christmas

Chronometers

Cicadas

Cinco De Mayo

Ciphers

Circle

Citizenship

Civil Rights

Civil Rights Movements

Civil War

Civil War - US

Climate

Climate Change

Clocks And Watches

Clouds

Cobb Vicki

COBOL (Computer Language)

Code And Cipher Stories

Collard III Sneed B.

Collectors And Collecting

Color

Commerce

Communication

Competition

Compilers

Composers

Computers

Congressional Gold Medal

Consitution

Contests

Contraltos

Coolidge Calvin

Cooling

Corms

Corn

Counterfeiters

Covid-19

Crocodiles

Cryptography

Culture

Darwin Charles

Declaration Of Independence

Decomposition

Decompression Sickness

Deep-sea Animals

Deer

De Medici Catherine

Design

Detectives

Dickens Charles

Disasters

Discrimination

Diseases

Disney Walt

DNA

Dogs

Dollar

Dolphins

Douglass Frederick 1818-1895

Droughts

Dr. Suess

Dunphy Madeleine

Ear

Earth

Earthquakes

Ecology

Economics

Ecosystem

Edison Thomas A

Education

Egypt

Eiffel-gustave-18321923

Eiffel-tower

Einstein-albert

Elephants

Elk

Emancipationproclamation

Endangered Species

Endangered-species

Energy

Engineering

England

Englishlanguage-arts

Entomology

Environmental-protection

Environmental-science

Equinox

Erie-canal

Etymology

Europe

European-history

Evolution

Experiments

Explorers

Explosions

Exports

Extinction

Extinction-biology

Eye

Fairs

Fawkes-guy

Federalgovernment

Film

Fires

Fishes

Flight

Floods

Flowers

Flute

Food

Food-chains

Foodpreservation

Foodsupply

Food-supply

Football

Forceandenergy

Force-and-energy

Forensicscienceandmedicine

Forensic Science And Medicine

Fossils

Foundlings

France

Francoprussian-war

Freedom

Freedomofspeech

French-revolution

Friction

Frogs

Frontier

Frontier-and-pioneer-life

Frozenfoods

Fugitiveslaves

Fultonrobert

Galapagos-islands

Galleys

Gametheory

Gaudi-antoni-18521926

Gender

Generals

Genes

Genetics

Geography

Geology

Geometry

Geysers

Ghosts

Giraffe

Glaciers

Glaucoma

Gliders-aeronautics

Global-warming

Gods-goddesses

Gold-mines-and-mining

Government

Grant-ulysses-s

Grasshoppers

Gravity

Great-britain

Great-depression

Greece

Greek-letters

Greenberg Jan

Hair

Halloween

Handel-george-frederic

Harness Cheryl

Harrison-john-16931776

Health-wellness

Hearing

Hearing-aids

Hearst-william-randolph

Henry-iv-king-of-england

Herbivores

Hip Hop

History

History-19th-century

History-france

History-world

Hitler-adolph

Hoaxes

Holidays

Hollihan Kerrie Logan

Homestead-law

Hopper-grace

Horses

Hot Air Balloons

Hot-air-balloons

Housing

Huguenots

Human Body

Hurricanes

Ice

Icebergs

Illustration

Imagery

Imhotep

Imperialism

Indian-code-talkers

Indonesia

Industrialization

Industrial-revolution

Inquisition

Insects

Insulation

Intelligence

Interstatecommerce

Interviewing

Inventions

Inventors

Irrational-numbers

Irrigation

Islands

Jacksonandrew

Jazz

Jeffersonthomas

Jefferson-thomas

Jemisonmae

Jenkins-steve

Jet-stream

Johnsonlyndonb

Jokes

Journalism

Keeling-charles-d

Kennedyjohnf

Kenya

Kidnapping

Kingmartinlutherjr19291968

Kingmartinlutherjr19291968d6528702d6

Kings-and-rulers

Kings Queens

Kings-queens

Koala

Labor

Labor Policy

Lafayette Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert Du Motier Marquis De 17571834

Landscapes

Languages-and-culture

Law-enforcement

Layfayette

Levers

Levinson Cynthia

Lewis And Clark Expedition (1804-1806)

Lewis Edmonia

Liberty

Lift (Aerodynamics)

Light

Lindbergh Charles

Liszt Franz

Literary Devices

Literature

Lizards

Longitude

Louis XIV King Of France

Lumber

Lunar Calendar

Lynching

Macaws

Madison-dolley

Madison-james

Madison-james

Mammals

Maneta-norman

Maneta-norman

Marathon-greece

Marine-biology

Marine-biology

Marines

Marsupials

Martial-arts

Marx-trish

Mass

Massachusetts-maritime-academy

Mass-media

Mastodons

Mathematics

May-day

Mcclafferty-carla-killough

Mcclafferty-carla-killough

Mckinley-william

Measurement

Mechanics

Media-literacy

Media-literacy

Medicine

Memoir

Memorial-day

Metaphor

Meteorology

Mexico

Mickey-mouse

Microscopy

Middle-west

Migration

Military

Miners

Mississippi

Molasses

Monarchy

Monsters

Montgomery

Montgomery-bus-boycott-19551956

Montgomery-heather-l

Monuments

Moon

Moran-thomas

Morsecode

Morsesamuel

Moss-marissa

Moss-marissa

Motion

Motion-pictures

Mummies

Munro-roxie

Munro-roxie

Musclestrength

Museums

Music

Muslims

Mythologygreek

Nanofibers

Nanotechnology

Nathan-amy

Nathan-amy

Nationalfootballleague

Nationalparksandreserves

Nativeamericans

Native-americans

Native-americans

Naturalhistory

Naturalists

Nature

Nauticalcharts

Nauticalinstruments

Navajoindians

Navigation

Navy

Ncaafootball

Nervoussystem

Newdeal19331939

Newman-aline

Newman-aline

Newton-isaac

New-york-city

Nobelprizewinners

Nomads

Nonfictionnarrative

Nutrition

Nylon

Nymphs-insects

Oaths Of Office

Occupations

Ocean

Ocean-liners

Olympics

Omnivores

Optics

Origami

Origin

Orphans

Ottomanempire

Painters

Painting

Paleontology

Pandemic

Paper-airplanes

Parksrosa19132005

Parrots

Passiveresistance

Patent Dorothy Hinshaw

Peerreview

Penguins

Persistence

Personalnarrative

Personification

Pets

Photography

Physics

Pi

Pigeons

Pilots

Pinkertonallan

Pirates

Plague

Plains

Plainsindians

Planets

Plantbreeding

Plants

Plastics

Poaching

Poetry

Poisons

Poland

Police

Political-parties

Pollen

Pollution

Polo-marco

Populism

Portraits

Predation

Predators

Presidentialmedaloffreedom

Presidents

Prey

Prey-predators

Prey-predators

Prime-meridian

Pringle Laurence

Prohibition

Proteins

Protestandsocialmovements

Protestants

Protestsongs

Punishment

Pyramids

Questioning

Radio

Railroad

Rainforests

Rappaport-doreen

Ratio

Reading

Realism

Recipes

Recycling

Refrigerators

Reich-susanna

Religion

Renaissance

Reproduction

Reptiles

Reservoirs

Rheumatoidarthritis

Rhythm-and-blues-music

Rice

Rivers

Roaringtwenties

Roosevelteleanor

Rooseveltfranklind

Roosevelt-franklin-d

Roosevelt-theodore

Running

Russia

Safety

Sanitation

Schwartz David M

Science

Scientificmethod

Scientists

Scottrobert

Sculpture

Sculpturegardens

Sea-level

Seals

Seals-animals

Secretariesofstate

Secretservice

Seeds

Segregation

Segregationineducation

Sensessensation

September11terroristattacks2001

Seuss

Sextant

Shackletonernest

Shawneeindians

Ships

Shortstories

Silkworms

Simple-machines

Singers

Siy Alexandra

Slavery

Smuggling

Snakes

Socialchange

Social-change

Socialjustice

Social-justice

Socialstudies

Social-studies

Social-studies

Sodhouses

Solarsystem

Sound

Southeast-asia

Soybean

Space Travelers

Spain

Speech

Speed

Spiders

Spies

Spiritualssongs

Sports

Sports-history

Sports-science

Spring

Squirrels

Statue-of-liberty

STEM

Storms

Strategy

Sugar

Sumatra

Summer

Superbowl

Surgery

Survival

Swanson-jennifer

Swinburne Stephen R.

Synthetic-drugs

Taiwan

Tardigrada

Tasmania

Tasmanian Devil

Tasmanian-devil

Technology

Tecumsehshawneechief

Telegraph-wireless

Temperature

Tennis

Terrorism

Thomas Peggy

Thompson Laurie Ann

Time

Titanic

Tombs

Tortoises

Towle Sarah

Transcontinental-flights

Transportation

Travel

Trees

Trung Sisters Rebellion

Tundra

Turnips

Turtles

Typhoons

Underground Railroad

Us-environmental-protection-agency

Us History

Us-history

Ushistoryrevolution

Us History Revolution

Us-history-war-of-1812

Us Presidents

Ussupremecourtlandmarkcases

Vacations

Vaccines

Vangoghvincent

Vegetables

Venom

Vietnam

Viruses

Visual-literacy

Volcanoes

Voting-rghts

War

Warne-kate

Warren Andrea

Washington-dc

Washington George

Water

Water-currents

Wax-figures

Weapons

Weather

Weatherford Carole Boston

Whiting Jim

Wildfires

Winds

Windsor-castle

Wolves

Woman In History

Women

Women Airforce Service Pilots

Women-airforce-service-pilots

Womeninhistory

Women In History

Women-in-science

Women's History

Womens-roles-through-history

Wonder

Woodson-carter-godwin-18751950

World-war-i

World War Ii

World-war-ii

Wright Brothers

Writing

Writing-skills

Wwi

Xrays

Yellowstone-national-park

Zaunders Bo

ArchivesMarch 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

December 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

September 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

March 2017

The NONFICTION MINUTE, Authors on Call, and. the iNK Books & Media Store are divisions of iNK THINK TANK INC.

a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit corporation. To return to the iNK Think Tank landing page click the icon or the link below. :

http://inkthinktank.org/

For more information or support, contact thoughts@inkthinktank.org

For Privacy Policy, go to

Privacy Policy

© COPYRIGHT the Nonfiction Minute 2020.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This site uses cookies to personalize your experience, analyze site usage, and offer tailored promotions. www.youronlinechoices.eu

Remind me later

Archives

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

September 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

January 2020

October 2019

August 2019

July 2019

May 2019

April 2019

December 2018

September 2018

June 2018

May 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed