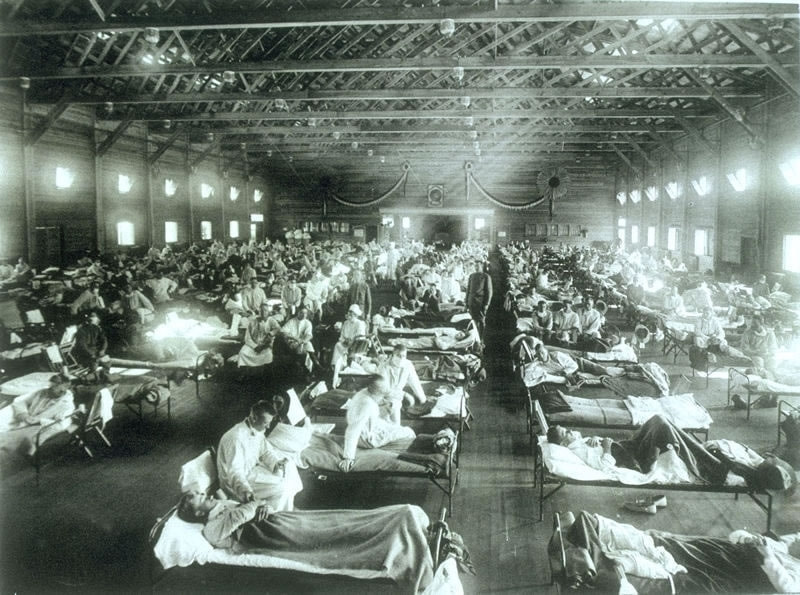

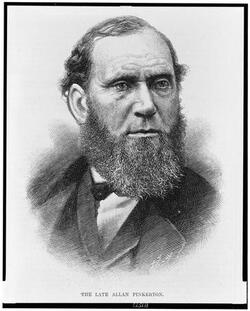

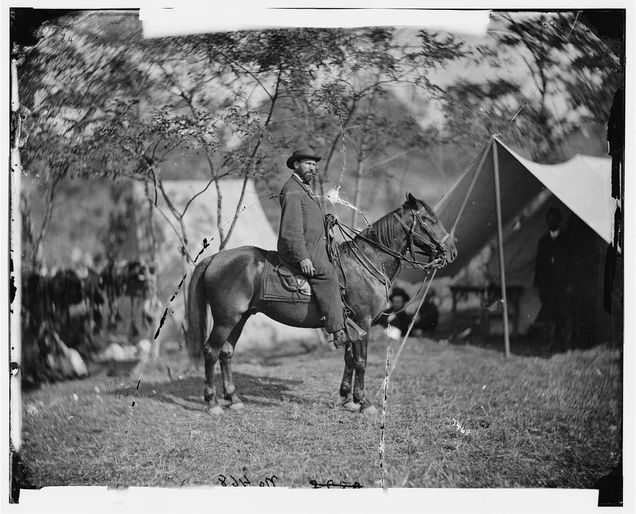

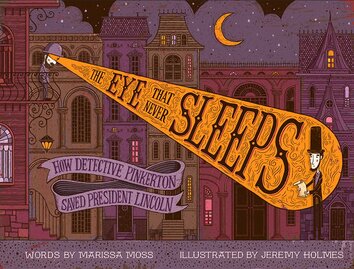

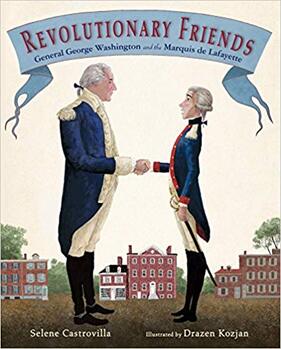

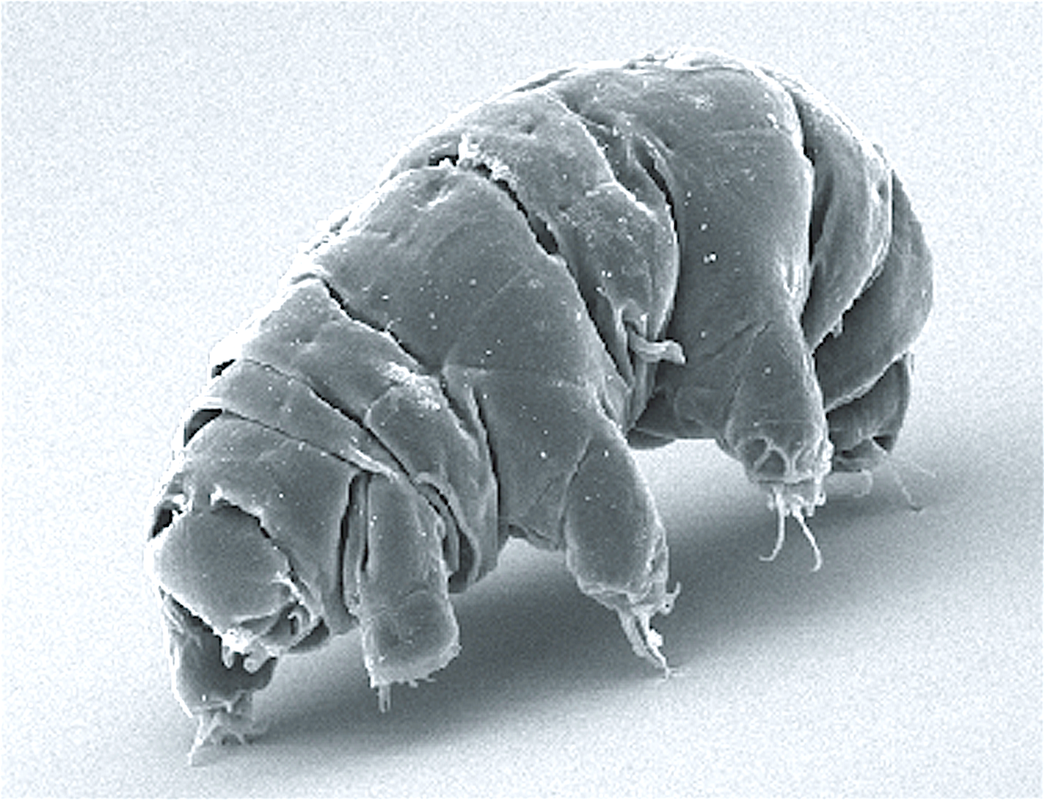

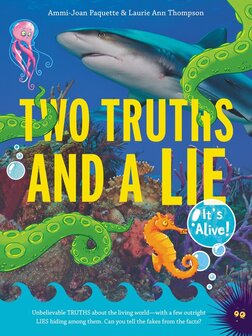

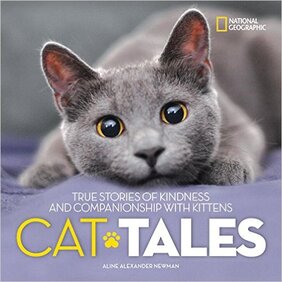

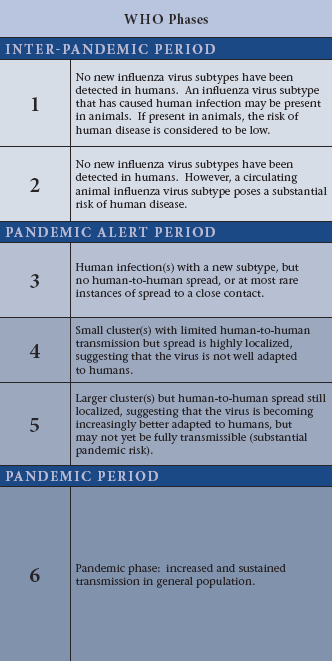

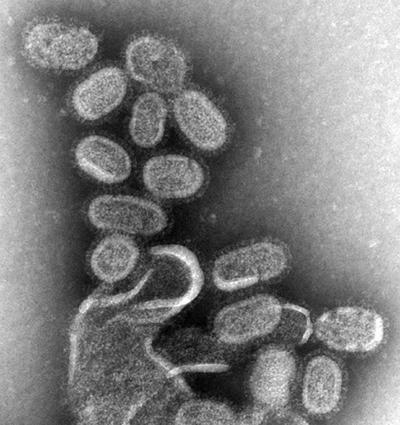

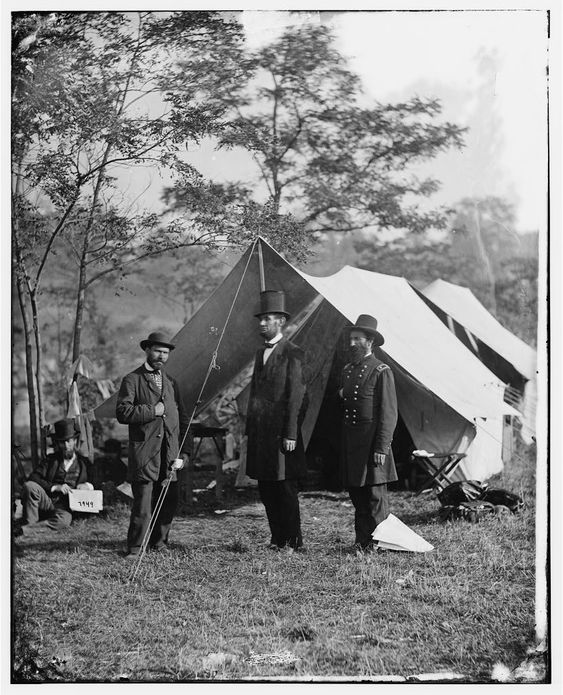

Huh? What does the flu have to do with the US Constitution? Here’s what. The 2017-2018 influenza season shaped up to be the worst on record since 1918, the infamous year when 20 to 50 million victims died of this highly infectious disease worldwide. By mid-season January 2018, the most common type, A(H3), was already widespread throughout forty-nine states and Puerto Rico. Doctor visits were three times higher than normal. And, the proportion of deaths continued to increase sharply. Warnings about the flu’s spread and severity and advice on how to try to avoid it appeared frequently in the media. Fortunately, the flu vaccine reduced the chance of catching the virus and eased symptoms of those who did come down with it, even though the vaccine had been engineered for a different strain. But, what if the disease threatened to fell millions of Americans, overrunning hospitals, closing schools and businesses, and causing panic? Could the government contain its reach by forcibly quarantining people? After all, that’s what some governors did in 2014 when they feared Ebola might run rampant here. Or, might the president or the Federal Aviation Authority halt flights to Hawaii, Alaska or Puerto Rico to at least contain it within the contiguous forty-eight states? Unfortunately, our Constitution is vague about the situations under which the government can detain people during such a state of emergency. Normally, habeas corpus applies. This provision says that people have the right to be released from detention if the government can’t supply a reason to keep them locked up. In 1787, when our Constitution was being drafted, the Framers debated whether there should be any exceptions to this right. Were there any grounds, they wondered, for keeping people confined for no legal reason and with no hope for release? They decided that “in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.” But, a pandemic of bird flu from China, say, never occurred to the Framers. Would that be considered an invasion? More recently, Congress gave the president the power to declare certain diseases “quarantinable” and to order the “apprehension…of individuals…for the purpose of preventing the introduction, transmission, or spread of such communicable diseases.” This is one of the government’s “police powers.” There are genuine questions, however, about what counts as such a disease and at what point in its spread the authorities can intervene. These are serious issues to consider—before an epidemic arrives.  Soldiers from Fort Riley Kansas lie ill with Spanish influenza at a hospital ward. It was the most famous and lethal flu outbreak ever to strike the United States, lasting from 1918 to 1919. It is not known exactly how many it killed, but estimates range from 50 to 100 million people worldwide. -Courtesy National Museum of Health and Medicine, AFIP (Washington, D.C.)  Many of the political issues we struggle with today have their roots in the US Constitution. Husband-and-wife team Cynthia and Sanford Levinson take readers back to the creation of this historic document and discuss how contemporary problems were first introduced―then they offer possible solutions. "A fascinating, thoughtful, and provocative look at what in the Constitution keeps the United States from being “a more perfect union.” " Kirkus Reviews - Best Middle Grade Nonfiction of 2017  In the mid-nineteenth century, a young man named Allan Pinkerton fled Scotland with a warrant on his head for his work agitating for labor rights. In the United States, he continued to fight for social justice. Beginning in 1844, he worked for Chicago Abolitionist leaders and his home outside of Chicago was a stop on the Underground Railroad. He was a close friend and ardent supporter of John Brown, helping him get runaway slaves to Canada. He was working as a barrel maker when he stumbled on a gang of counterfeiters. His handling of that incident began his career as a crime-solver, and in 1849, he was hired to be the first detective on the Chicago police force. Detective work was considered sleazy at that time—a way of profiting from other’s crimes. Pinkerton gave it a new meaning by making justice his mission. He created careful “detecting methods,” using psychology, logic, and clear thinking. These tools worked, and a year later, Pinkerton was able to set up his own company known as the North-Western Police Agency. This later became Pinkerton & Co. and then the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. In October, 1856 Pinkerton hired Kate Warne as the first woman detective in the United States. He was so impressed with her skill that he hired many other women (fifty years before any police department in America had female personnel.) While Pinkerton insisted that detectives must combine “considerable intellectual power and knowledge of human nature,” he discouraged them from pressuring confessions or taking statements from witnesses who were drunk. Above everything else, he valued the truth. Pinkerton ran the new spy agency, the Secret Service, for President Lincoln during the Civil War the same way he'd run his detective agency. He honed the art of “spycraft” and trained his agents the same way for both jobs, detective and spy. “The object of every investigation. . .is to come at the whole truth. . .There must be no endeavoring, therefore, to over-color or exaggerate anything against any particular individual, whatever the suspicion may be against him.” Pinkerton was working on a national criminal database when he died, but he left behind the legacy of his intelligence agency and a series of popular books about his cases, the first “true crime” stories in America.  Left: A wood engraving of Pinkerton published in "Harper's Weekly" magazine in July 1884, the month of his death. Library of Congress Below: The Pinkerton Agency's iconic logo—a large, unblinking eye accompanied by the slogan “We Never Sleep”—gave rise to the term “private eye” as a nickname for detectives.  Pinkerton is shown on horseback on the Antietam Battlefield in 1862. Pinkerton served on several undercover missions as a Union soldier using the alias Major E.J. Allen. This counterintelligence work done by Pinkerton and his agents is comparable to the work done by today's U. S. Army Counterintelligence Special Agents in which Pinkerton's agency is considered an early predecessor. Library of Congress  Award-winning author Marissa Moss has written the first children’s book about Allan Pinkerton. Everyone knows the story of Abraham Lincoln, but few know anything about the spy who saved him! Pinkerton had a successful detective agency, but his greatest contribution was protecting Abraham Lincoln on the way to his 1861 inauguration. Though assassins attempted to murder Lincoln en route, Pinkerton foiled their plot and brought the president safely to the capital. The Eye That Never Sleeps is illustrated with a contemporary cartoon style and includes a bibliography and a timeline.  “My heart was enlisted,” the Marquis de Lafayette wrote in his memoirs, “and I thought only of joining my colors to those of the revolutionaries.” Who were the revolutionaries Lafayette referred to? Americans, bien sûr! Lafayette was just 19 when he paid for his ship, hired a crew and set sail from France to attach his colors to ours. He defied his king, who denied him permission to leave, and left his pregnant wife and child behind. Seasick every day of his month-long voyage, he nevertheless learned English along the way. Docking at Charleston, NC, he trekked hundreds of miles to Philadelphia, suffering a month of broken carriages, lame horses, and nightly mosquito raids. He remained buoyant, and dedicated to our fight. Finally at Continental Congress, he enthusiastically introduced himself—only to be turned away. There were too many foreign officers, they told him. S'il vous plaît, Lafayette pleaded. He’d come so far—and he would work for free. They accepted his services, but refused to give him what he yearned for: troops to command. At least Lafayette could stay—and meet his idol, Commander-in-Chief George Washington! Lafayette felt an instant connection with Washington, who invited the young Frenchman to live with him. Washington was diplomatic. He knew Lafayette was of noble descent, and he needed France’s aid in order to win the revolution. But Lafayette mistook the invitation for affection. “I am established in his house, and we live together like two attached brothers…” he wrote his wife. It wouldn’t be long before Washington felt genuine affection for Lafayette. As the situation in Philadelphia grew dire—they were surrounded by the British and awaited an inevitable attack—Washington took a moment to have a “great conversation” with Lafayette. Think of me as your father, he told him. Lafayette was touched in the deepest way. At the Battle of Brandywine, the Americans were overwhelmed and defeated. Our soldiers panicked—deserting their lines. Lafayette requested permission to rally the troops. Though he feared for Lafayette’s life, Washington granted his wish. Lafayette’s great spirit convinced the troops to stay. The Americans still had an army, to fight another day. A musket ball ripped through Lafayette’s leg! He eventually collapsed. Back at headquarters, Washington instructed his personal physician, “Treat [Lafayette] as if he were my son. For I love him the same.”  The father/son relationship of George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette developed while they were under British siege. A multiple award-winning choice in history books for kids, and a compelling account in American history by a research-loving writer! You can buy it here.   Would you like this fellow waiting for you in your garage? Would you like this fellow waiting for you in your garage? When I was about 10 years old, I lived in a small town on a prairie. I had to walk to and from school each day taking a short cut through our dark, crowded garage. This was fine until the spiders set up home in each corner of the garage-door opening, spinning huge blobs of flimsy webs, hanging there, ready to drop on my head or down my back. I ran under them to the safety of the alley. They feasted on Minnesota’s mosquitoes, growing to what I imagined to be tennis ball-sized bodies with red and yellow stripes, long, thick hairy legs, and large bulb-like eyes. My brother and sister thought they were monsters; we shudder when we remember them. But actually they were wolf spiders because like wolves, they’re predators. They lie in wait for prey to come close. Then they chase and pounce on it, stinging it with their venom that dissolves the organs so the spider can suck up the nourishment. In March of 2012, wolf spiders made news in Wagga Wagga, Australia, a town of 50,000 a few hours south of Sydney, Australia’s largest city. Some say due to climate change, it rained much more than usual, causing the river, peacefully flowing through the town, to flood the fields. It flooded the hibernation holes of the wolf spiders, which they had dug a few months earlier in the sun-baked ground and lined with silk, ready for the coming winter. The floodwaters woke up the spiders, which fled for higher ground, bushes, trees, houses, poles, any high places. As more than a million spiders ran they trailed behind “drag lines” of silk that caught the wind lifting some of them through the air. Countless thin trails of silk covered the bushes and fields, creating a blanket of web, looking like snow. No one had seen anything like it. When I read it about it, I knew instantly that this was the spider that terrorized me as a child. Wolf spiders are found all over the world, in Minnesota and Australia. I believe that this was a small whisper from the earth about what is happening to it. If this damage in Wagga Wagga was caused by climate change, imagine the invasions and changes that may yet come. The next even could be a shout.  Trish Marx has authored some terrific nonfiction titles. Check out Everglades Forever for some more high interest reading about animal behavior.  Are you tougher than a tardigrade? I don’t think so. These typically water-dwelling animals may be microscopic in size (barely half of a millimeter when fully grown!), but boy are they fierce. Sometimes called “water bears,” they’re anything but cuddly. Each of their eight legs is decked out with wicked claws. Some tardigrades have full body armor. Most have specialized "sucker" mouths to pierce the cells of plants and animals and suck out their nutrients, while others prefer to consume their tiny prey whole… and that prey might even be another tardigrade! Aside from ending up as someone else’s dinner, though, tardigrades are practically indestructible. They can survive in just about any conditions and take on just about anything life has in store for them. Starvation? No worries there: Tardigrades can go without food for at least 10 years. What about water, you say? No problem. They’ll just suspend their life activities and wait until the drought is over. They can survive at pressures more than six times that of the deepest ocean trenches. And, you’d die from radiation poisoning long before a tardigrade would even notice. Scientists have even tried shooting them into outer space… and the tardigrades survived. Because of their ability to live practically anywhere, these little guys are practically everywhere. Tardigrades can be found on top of Mount Everest and in boiling hot springs, in desert dunes and rainforest canopies, in freshwater lakes and salty oceans, on your roof, outside your front door… maybe even in your bed or on your dinner plate! There are billions and billions of tardigrades… and they’re always making more! Fortunately, there’s no need to worry—tardigrades are completely harmless to humans. In fact, tardigrades may actually end up being our best friends someday. Because they can do so many things that other Earthly animals can’t, scientists are studying tardigrades to try to find solutions to all kinds of problems. Want to dry something out to preserve it, then rehydrate it later? Study how tardigrades do it. Wish we could safely reanimate something that has been frozen? Learn from the tardigrades. Need to protect cells from being damaged by radiation? Figure out why tardigrade cells can withstand it. Who knows? Someday the tough tardigrades might teach us all kinds of handy tricks!  An adult Milnesium tardigrade, an example of more than 1,000 species of the tiny animal. Bob Goldstein and Vicky Madden, UNC Chapel Hill/Wikimedia Common An adult Milnesium tardigrade, an example of more than 1,000 species of the tiny animal. Bob Goldstein and Vicky Madden, UNC Chapel Hill/Wikimedia Common This video shows a tardigrade in real time at 100X magnification. Dmitry Brant via Wikimedia Commons  Laurie Ann Thompson and coauthor Ammi-Joan Paquette begin a fascinating new series with Two Truths and a Lie, a book that presents some of the most crazy-but-true stories about the living world. Some of the stories are too crazy to be true—and readers are asked to separate facts from fakes! "A brief but savvy guide to responsible research methods adds further luster to this crowd pleaser.” —ALA Booklist (starred review)  Percy the coal black cat is a born wanderer. The former barn cat sleeps by the woodstove in winter. But in summer, he leaves after breakfast and stays out all night. For years, his owners, Anne and Yale Michael, never knew where he went. Then a friend called to tell them that Percy had made the front page of the local newspaper. The Michaels live in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, in the United Kingdom, a pretty seaside town on the Atlantic coast. Tourists flock there in summer to go to the beach and ride the miniature train that runs along it. According to the newspaper, their Percy was also riding the rails! “We were shocked,” Yale says. “I wondered if it was really our cat.” Because the frisky feline was always losing his collar and tags, no one knew who owned Percy or where he lived. But after their friend recognized him in that front-page newspaper article, radio and television stories followed. Percy became famous. The train station is half a mile (0.8 km) from the Michaels’ home. To get there, Percy has to walk down the alley beside their house and cross the neighbor’s yard and a golf club parking lot (where he occasionally stops for meaty handouts). Finally, he trots over to the sea cliff and through some woods down to the railway. Once Percy arrives at the train station, he dozes on a mat the railway workers have laid out for him until he hears the train whistle. Then, every day, he boards the train, takes a seat, and rides to the Sea Life Centre. Perhaps the smell of fish drew him there originally. But that isn’t why he visits now. The curious cat behaves like any human tourist and visits the marine sanctuary to view the exhibits. The penguins are his favorite. Percy might watch them strut about for half an hour, before he strolls into the office where aquarium workers have been welcoming him for years. When it’s time to leave, the furry penguin watcher hops back on the train for the trip home. The Michaels rode the tourist train once. “He got off, as we got on,” says Yale. “We said, ‘Hi, Percy.’“ He turned around and came to us.” But only in greeting. Then their popular, wandering pet continued on his independent way. Now that they know about his daytime adventures, they’re waiting to hear what he does at night. Perhaps a local disco?  Percy’s choice of transit: The North Bay Railroad running from Scarborough to the Sea Life Centre. Percy’s choice of transit: The North Bay Railroad running from Scarborough to the Sea Life Centre.  Aline Alexander Newman is a lifelong animal lover who has written more than 50 magazine stories about animals from dogs to cheetahs to dolphins. Her love of cats is reflected in her recently published Cat Tales: True Stories of Kindness and Companionship with Kittens.  Writing a recipe is harder than it looks. I found this out when a children’s magazine editor asked me to add a recipe to my article about eating insects. First, I thumbed through my recipe file mentally substituting bugs for a vital ingredient. Mushrooms stuffed with millipedes was out. (Most kids don’t like mushrooms.) I nixed beetle sausage, also. (Too much chopping and frying in a hot skillet.) Flipping to desserts, I chose toffee. I could substitute bugs for nuts. After my trip to the grocery store for butter, sugar and chocolate chips, I visited the pet shop, and asked for a cup of mealworms, which are fly larvae (also known as maggots, but that’s not very appetizing). The man handed me a little carton that looked like a Skippy cup of ice cream. I wrote that down because I would need to pass that information on to readers who, like me, had no clue how to purchase creepy-crawlies. With all the ingredients on the counter I recorded each step:

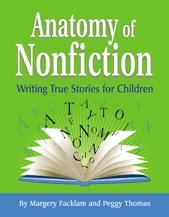

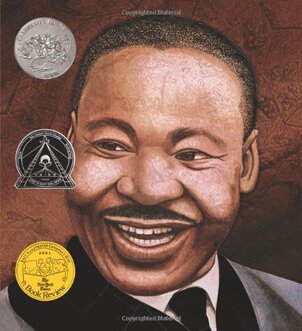

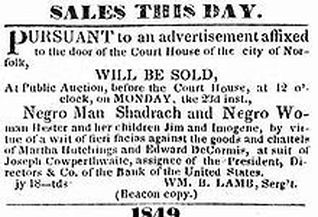

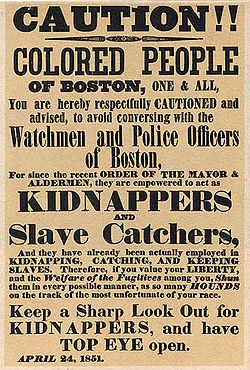

After that, I was on familiar ground blending butter and sugar, and sprinkling chocolate chips. I called my concoction Toffee Surprise, and taste-tested it in a large group setting where peer pressure encouraged full participation -- my mother’s birthday party! The verdict: The toffee was yummy, crunchy, and sweet with a subtle earthy aftertaste. Although I don’t plan on cooking more edible vermin, I did learn some important rules for writing a recipe: Choose a food that is reader-friendly; be aware of your readers’ abilities and safety issues; record every step in order; pay attention to even the smallest details; and prepare it yourself so you can work out the bugs (no pun intended).  Peggy Thomas is the co-author of Anatomy of Nonfiction, the only writer's guide for children's nonfiction. To find out more about Peggy, visit her website. She also has a blog for writers, based on the book. Peggy Thomas is a member of iNK's Authors on Call and is available for classroom programs through FieldTripZoom, a terrific technology that requires only a computer, wifi, and a webcam. Click here to find out more.  Seven white guards ringed the courtroom. Two more stood at Shadrach Minkins’ side. His lawyer Robert Morris, a black member of the Boston Vigilance Committee, a group of abolitionists who helped runaway slaves like Minkins, talked softly to him. Five other white men, who were also abolitionists stood behind Morris. Shadrach appreciated their support but he knew it wouldn’t matter. His three months of freedom in Boston, Massachusetts were over; he would be dragged back to Norfolk, Virginia and his owner, John DeBree. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 had been passed a year earlier: if runaway slaves were tracked down in the free states, they had to be returned to their owners. The guards started letting a few people at a time into the courtroom until it was packed with over a hundred and fifty black men and about fifty white men. Morris went up with DeBree’s lawyer to speak to the judge. “I need more time to prepare my client’s case,” Morris told the judge. Debree’s lawyer protested. The judge agreed to give Morris a few more days. Then he ordered the courtroom cleared. Most of the white men hurried out. Not one black man moved. “Clear the court!" the bailiff shouted. No one moved. The guards walked threateningly toward the black spectators, and they reluctantly got up to leave. The guard opened the courtroom door just wide enough for one man at a time to get out. Shadrach watched them leave. Morris was the last. When the door was opened for him, twenty black men and a good number of whites pushed into the courtroom. The guards on either side of Shadrach pressed him close. The seven guards along the wall tried to move toward Shadrach, but the crowd moved more quickly and pressed them back. Two men hoisted Shadrach to his feet. “Take him out the side door,” someone shouted. A guard’s voice echoed in Shadrach's ears as the crowd ran triumphantly out the side courtroom door, down the stairs, out into the street with their prize. Five days later, on February 20, 1851, Shadrach arrived in Canada shepherded by various Underground Railroad conductors along the way. His rescue caused an uproar. Southerners demanded an investigation. Northern abolitionists insisted the Fugitive Slave Act was illegal. Eight men, including Morris were arrested, but the charges were dropped. Eighteen months later Shadrach was married and running a barber shop in Montreal.  Doreen Rappaport is known for her ground-breaking approach to multicultural history and stories for young readers. In her many award-winning books, she brings attention to not-yet-celebrated Americans, along with well-known figures. Her book Martin's Big Words: The Life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is an Orbis Pictus Honor Book, Coretta Scott King Honor Book, Caldecott Honor Book for Illustration, and an ALA Notable Book. For more information, click here. And while you're on Doreen Rappaport's website, look at the list of her African-American History books.  “Where am I?” The smiling young pilot was apparently nonplussed. He had landed at Dublin’s airport without a permit – or even a passport – and was now confronting several frowning custom officers. “I took off from New York with the intention of flying to Los Angeles,” he explained. “After twenty-six hours coming down through the clouds I was puzzled to see water instead of land. I must have misread my compass and followed the wrong end of the needle.” The Irish, never averse to a good yarn, looked at his primitive plane and cheered him for his audacity. When word of his remarkable flight reached the United States, the pilot, Douglas Corrigan, became known as “Wrong Way” Corrigan. The story of Corrigan, an Irish-American mechanic, has been called an Irish fairy tale, an impish yarn spun with a straight face. It unfolded in 1938 but really began when Corrigan, at age twenty, worked on the team that built The Spirit of Saint Louis, the plane that took Charles Lindberg across the Atlantic. Lindberg became Corrigan’s hero. His dream: to make that same flight himself. But Corrigan was just an ordinary guy struggling to make ends meet. Still, he managed to get a pilot’s license, and began flying in his spare time. In 1931 he bought his own plane. It was a battered old machine, but Corrigan loved it, and radically changed it, so that, one day, he would be able to duplicate his hero’s transatlantic flight. He was set to go – except for one major obstacle: more stringent regulations for trips overseas. Applying for a government permit, he was turned down because his plane was too old. Then, in 1938, he got a license for flights between Los Angeles and New York. Seeing him him take off for Los Angeles, people wondered why he headed northeast instead of west. The world laughed - an unlikely hero, a mirthful, courageous individual who thumbed his nose at authority. Back in New York, Corrigan was treated to a ticker-tape parade on Broadway. A nationwide tour followed. He met with President Roosevelt, received membership in the Liar’s Club in Wisconsin, was hailed as “Chief Wrong Way” by a Native American tribe, showered with compasses, and given a watch that ran backward. Asked about his flight, his response was always the same: a grin and “Man, I didn’t mean to do this at all.”  Bo Zaunders has written four nonfiction books for children and illustrated two. He is also a photographer specializing in food and travel. Like Corrigan, he loves adventures. You can find Feathers, Flaps & Flops in the iNK Books & Media Store. |

The Nonfiction Minute returns on 9/12/20.We publish the Minutes for the coming week on Saturdays so teachers can make plans and we update the Minute for each day, so a new Minute appears at the top of the queue. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed