|

0 Comments

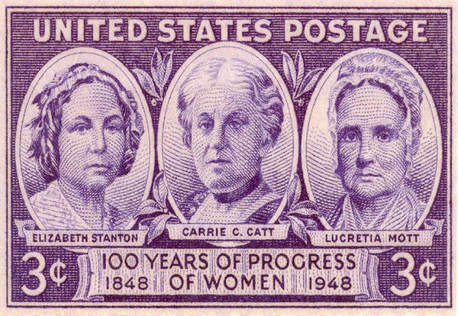

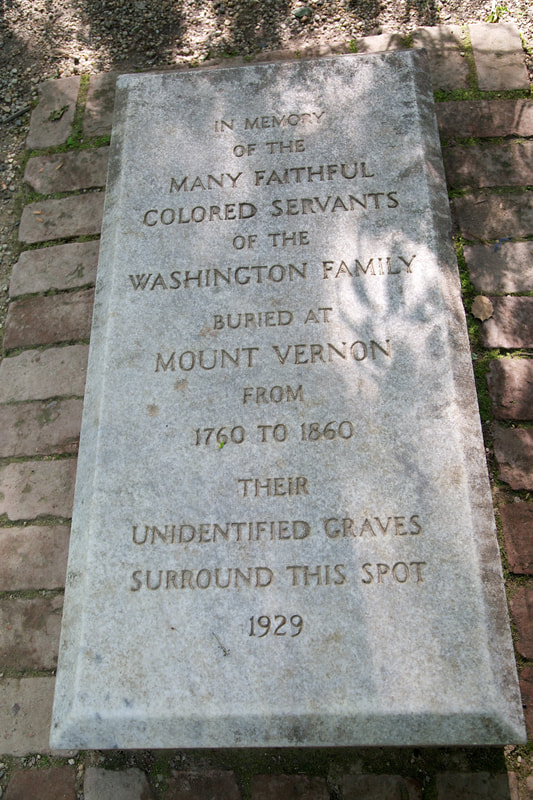

History happens everywhere—even your own backyard. Have you ever heard of Carrie Chapman Catt? From 1919-1928 Carrie lived in a house near mine called Juniper Ledge. She was a suffragist, one of many who fought for women’s right to vote. Without her, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which gave women the vote, might never have been approved. Born in 1859 and raised in Iowa, Carrie got an early lesson in politics when she asked why her mother wasn’t voting in the 1872 presidential election. Everyone laughed, but not Carrie. She thought it unfair that women couldn’t vote—and wasn’t afraid to say so. In college Carrie joined a literary society. Women were forbidden from speaking during meetings. After Carrie spoke at a debate, the rules were changed to allow women’s participation. A woman of many “firsts,” Carrie worked as a teacher after graduation and became one of the first female school superintendents in the country. After marrying she moved to San Francisco. When her husband died she supported herself by working as that city’s first female newspaper reporter. Back in Iowa, Carrie joined the Iowa Woman Suffrage Association, part of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), led by Susan B. Anthony. Carrie’s rousing speeches brought her national attention. When Susan retired, Carrie became NAWSA’s president, leading suffrage campaigns all over the country and supervising a million volunteers. Carrie’s “Winning Plan” for the vote worked on both state and federal levels. She supported President Woodrow Wilson’s efforts in World War I, even though she was a peace activist. She knew if Wilson backed women’s suffrage, Congress would vote for it. And that’s exactly what happened. Carrie’s activism didn’t stop at the U.S. border. As founder and president of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance, she advocated for democracy and women’s rights on four continents. She also founded the League of Women Voters to educate women on political issues, worked for world peace, and campaigned against child labor and Hitler’s treatment of Jews. When the Nineteenth Amendment was approved in 1920, Carrie was living at Juniper Ledge. There she nailed plaques to trees in honor of women who fought for the vote. Juniper Ledge still stands, right down the street from the park where today kids play ball. Who knows what other people, places and stories from the past they may find in the neighborhood?  Susanna Reich lives in New York's Hudson River Valley, where her interests in social activism and local historical figures led her to write Stand Up and Sing!: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and the Path to Justice. She received the 2018 Rip Van Winkle Award for Outstanding Contributions to Children’s Literature.  Today (May 11)is World Migratory Bird Day—a holiday designed to celebrate the many birds that travel our globe. Why do birds migrate? Why don’t they just stay in the same place all year long? There are many reasons…warmer weather, better nesting sites, and more plentiful food are just a few. Some birds travel very short distances. One example is North America's dusky grouse. This bird spends its winter in mountainous pine forests. In the spring, it “migrates” a mere 1,000 feet in elevation to deciduous woodlands. Here it feeds on seeds and fresh leaves. And then there are birds that travel very long distances. One world traveler is the Arctic tern. This bird migrates an astonishing 44,000 miles annually from the Arctic to Antarctica and back again. And finally there are birds that travel distances in between those two extremes, like the turtle dove. This bird migrates about 8,000 miles a year. You might wonder how scientists know where birds go, and how they get such accurate data about the birds’ migrations. They do this by tracking birds using satellite telemetry. Birds are fitted with small satellite tags. These tags transmit information about their journeys to scientists via orbiting satellites. You can sometimes see these satellites on dark nights. They look like tiny stars moving very slowly across the sky. An environmental organization called the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) fitted a turtle dove named Titan with a satellite tag. Titan’s tag had a tiny satellite transmitter, a battery, and a solar panel to keep the battery charged. Using this technology, scientists were able to track three of Titan’s migrations. The first was in the fall. Titan flew from a nesting site in Suffolk, England down to his wintering site in Mali, in West Africa. The second was in the spring when Titan migrated back to Suffolk, England, to the very site where he was originally found! The third was in the fall when he migrated back to Mali again. After that trip, the scientists lost track of Titan. Let’s celebrate World Migratory Bird Day by learning more about migratory birds and what we can do to help protect them. Click here to view some actual turtle dove migrations.  Madeleine Dunphy has written a book based on the migration of a real turtle dove that traveled 4,000 miles from England to Mali, in West Africa. To find out more about The Turtle Dove’s Journey: A Story of Migration click here. You can read Vicki Cobb's review of the book here.  The shady spot overlooking the river didn’t look like a cemetery. Nothing marked it as a burial ground - no flowers, no grave markers, not even a sign. Yet buried there lay the remains of enslaved people of Mount Vernon, George Washington’s estate. Even knowledge of the cemetery’s location might have been lost to time if The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association hadn’t bought Mount Vernon in 1858. Just a few years later, the Civil War brought an end to slavery. At last, men, women and children would no longer be enslaved - or buried - at Mount Vernon. Years passed and the memory of who was buried there and where they were buried faded away. By 1929, The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association realized that even the location of the cemetery might soon be forgotten. They installed a marker to identify the site of the cemetery. More years passed. Weeds and underbrush grew over the unmarked graves-and the 1929 marker. At last in 1982 a memorial was installed to honor the people who were enslaved at Mount Vernon. For the first time the public had a place to pay their respects to those buried there. The gray granite column in the center of the memorial reads: Then in 2014, archeologists at Mount Vernon began an exciting new project. A multi-year archaeological dig that would answer three questions:

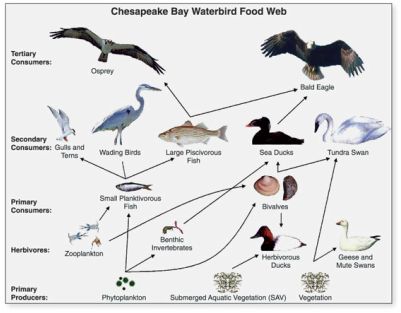

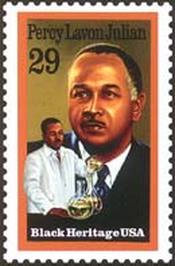

To accomplish the dig, archeologists remove six to eight inches of soil - only enough to determine if a grave is present. No human remains will ever be disturbed in the process. So far, more than 70 graves have been located – some of them graves of children. Like other slave owning families, the Washingtons did not keep birth, death or burial records of the people they enslaved. Today, it is impossible to know the identities of the individuals who lie in each grave. But this archaeological dig will at least allow us to know, and honor, the location of their final resting places. The individuals buried there may remain nameless, but they are not forgotten.  Do you want to find out how an archaeological dig works? In Buried Lives: The Enslaved People of George Washington’s Mount Vernon you will discover how they uncovered graves in the cemetery at Mount Vernon-and about six, specific real life enslaved people who served the Washington family. You can read Vicki Cobb's review here.   An 1835 Sketch of "Miss Wright." An 1835 Sketch of "Miss Wright." When she was a girl in Scotland, Frances or “Fanny” Wright fell in love with America, a new nation “consecrated to freedom.” On September 3, 1818, the 22-year-old writer set foot on that actual land of her dreams. She and her little sister Camilla, a pair of wealthy orphans, spent the next two years touring the young U.S. Young females did NOT go traveling without a man in those days, but Fanny believed that freedom should apply to women too! Her 1821 book about her travels won her the friendship of another freedom fan, the Marquis de Lafayette, who’d helped free America from the British Empire. In 1824, the old Frenchman made sure Fanny met his friend, 81-year-old Thomas Jefferson and his friend, 73-year-old James Madison. But wait – maybe you already see a fly in the soup. To Fanny, “slavery was revolting everywhere.” Slaves in the Land of Liberty was sickening! As much as she admired the two former presidents, she hated that they lived in slave-built mansions, waited on by people who had no choice but to do so. But slavery really did trouble them, too. Slavery trapped everyone in its evilness. With so much money tied up in costly human property, owners couldn’t afford to let them go. Could blacks support themselves, after lifetimes of being fed, housed, and denied education? Madison and Jefferson thought no; emancipation had to be gradual. Really, centuries of racial division had them and their countrymen thinking that the races could never live together. Surely blacks must go back to Africa! (In fact, many had already been sent there, to Monrovia, but that’s another story for another day.) So Fanny planned farms where blacks could learn while they earned their freedom money. It was her way of freeing her beloved America from the curse of slavery. She published her idea and tried to make it work on Nashoba, her own farm in Tennessee, but her experiment failed. Then, in the late 1820s, she went around the eastern US, making speeches about all of her freethinking ideas and shocking the daylights out of people. A public-speaking woman was unheard of! Going around, talking about abolition, day care for working mothers, the rights of women and factory workers? SHOCKING! That’s the thing to know about Fanny Wright: She was one stubborn radical, WAY ahead of her time, imagining freedoms she never lived to see.  Cheryl Harness has written (and illustrated) short, spirited profiles of twenty women who impacted life in America by speaking out against injustice and fighting for social improvements. The book spans over two hundred years of American history and includes time lines for such important social movements as abolition, woman suffrage, labor, and civil rights. Readers inspired by these fiery women can use the civil action tips and resources in the back of the book to do some of their own rabble-rousing. For more information, click here. In 1963, at a ceremony in Washington, D.C., President Lyndon Johnson awarded singer Marian Anderson the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest honor a president can give to a civilian (someone not in the military). He explained why this African American musician was being honored: “Artist and citizen, she has ennobled her race and her country, while her voice has enthralled the world.” Twenty-four years earlier, however, some in Washington weren’t interested in honoring her but instead treated her unfairly. By then, she had given wonderful concerts of classical music in Europe and the United States, including at the White House. But in 1939, when a local university tried to have her perform at Constitution Hall, Washington’s concert hall, the managers of Constitution Hall wouldn’t let her, just because of the color of her skin. Eleanor Roosevelt, President Franklin Roosevelt’s wife, was upset by this example of discrimination against African Americans and arranged for Marian Anderson to perform that spring at the Lincoln Memorial. More than 75,000 people filled the area in front of the memorial to hear Marian Anderson sing. Thousands more around the country listened on radio to a live broadcast of the performance. She started by singing “America,” then sang some classical pieces, and ended with spirituals, including “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Newspapers and magazines wrote rave reviews, which let thousands more people learn about the dignified and courageous way she had triumphed over discrimination. Four years later, in 1943, she was at last invited to perform at Constitution Hall. Did this end unfair treatment for this singer? Not exactly. In 1953, Marian Anderson was again denied permission to perform at a concert hall, this time by the Lyric Theater in Baltimore, Maryland. Luckily, this city’s music- and freedom-loving citizens came to her defense. Some wrote letters to newspapers complaining about “this insult to a great American singer.” Others threatened never to go to that concert hall again. Hundreds complained directly to the Lyric’s managers. Finally, Maryland’s commission on interracial relations persuaded the Lyric’s owners to let Marion Anderson perform there on January 8, 1954. The hall was filled to overflowing with her enthusiastic fans. Ten years later, racial discrimination in concert halls finally became illegal. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination based on race, religion, or national origin at any place that serves the public, including concert halls, theaters, stadiums, restaurants, hotels, and anywhere else. Source notes for this Minute may be found be clicking here.  Amy Nathan is the author of Round and Round Together: Taking a Merry-Go-Round Ride into the Civil Rights Movement, which tells about many little-known and yet important stories in civil rights history, including the story of Marian Anderson being the first African American to perform at Baltimore’s Lyric Theater in January 1954, and also the story about the merry-go-round that’s located not far from where Marian Anderson gave her famous 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. For more information, click here.   A long time ago in a land far, far away… The climate suddenly changes. It’s May, and a “Great Fog” appears in the sky. During the day it blocks out the sun and acts like a blanket trapping heat near the ground. A ten-year old boy notices that temperatures spike and sunsets are a spectacular display of colors. He doesn’t know that volcanoes in the “Ring of Fire” are spewing ash into the atmosphere creating massive clouds and causing the strange weather. All he knows is that he can’t take his eyes off the sky. The boy’s name is Luke Howard. The year is 1783, and his location is the English countryside. Luke records his observations in a journal. Although he doesn’t know it yet, he is on his way to becoming the “Father of Meteorology.” Flash forward twenty years. It’s 1803, and Luke Howard is a successful businessman. But in his spare time, ever since the summer of 1873, he’s been watching the clouds and thinking up new ideas about the weather. He writes and publishes a scientific paper and presents his ideas to a group of fellow amateur scientists. His article, “On the modification of clouds, and on the principles of their production, suspension and destruction,” classifies clouds into groups using Latin words: heaped (cumulus), layered (stratus), fibrous (cirrus), and rain (nimbus). By combining terms into names such as Cirro-cumulus, which he describes as "small, well-defined roundish masses, in close horizontal arrangement," Luke identifies many kinds of clouds. Luke’s passion for clouds inspires him to make watercolor sketches and write a book called The Climate of London, which introduces new ideas about lightening and the causes of rain. In 1864, Luke Howard dies at the age of ninety-two, leaving behind a cloud naming system that is still used today. A long time ago in a land far, far away, Luke Howard names the clouds—and in our imagination we see him turning to a friend and saying, “May the clouds be with you.”  Spidermania: Friends on the Web debunks myths about spiders and takes an extremely close look at creatures that have both fascinated and terrified humans. An introduction explains what makes spiders unique. Then ten species are highlighted with incredible electron micro-graph images and surprising facts. From diving bell spiders that live in bubbles underwater, to spitting spiders that shoot sticky streams of spit at their prey, to black widows and wolf spiders, this unusual book will intrigue readers and help cure arachnophobia. For more information, click here.  Are skunks aggressive, dangerous animals? Or are they peaceful animals that try to avoid trouble? Well, biologists who study skunks think of them this way: if life were a sport, skunks would be known for their strong defense and for playing fair. Skunk stinkiness comes from a chemical weapon called musk. Foxes, weasels, and some other mammals also produce musk, but skunk musk is especially strong and long-lasting. And only skunks use musk to defend themselves from attack. Picture a skunk ambling along in the night, looking for food. It digs in the soil to get tasty earthworms and beetle grubs. The black and white fur that comes with just being a skunk sends a warning. This color pattern is unusual among mammals. It signals: "Beware, don't mess with me!" Suppose a coyote or other predator ignores this first warning. It steps toward the skunk. When a skunk feels threatened, it faces the danger. It raises its tail and tries to look as big as possible. It stamps its feet and clicks its teeth together. It may growl or hiss. Oh, oh! Despite all of these warnings, the coyote growls and comes closer. Now the skunk gets really serious. It twists its body into a U-shape, so it can see the coyote and also aim its rear end toward it. The skunk's tail arches over its back, away from its rear—the final warning. This gives the skunk a clear shot, and also protects its own fur from the stinky musk. Skunks try to avoid smelling bad! From two grape-sized glands, a skunk can spray musk as a fine mist, or squirt a stream. It can squirt accurately for about 12 feet (3.7m), and hit an attacking animal right in the face. The musk stings the predator's eyes, and can blur its vision for a while. And it stinks! Animals hit with this musk learn to never bother a skunk again. A skunk's glands store enough musk to fire a half dozen shots but then need a week or so to produce more. This is seldom a problem, since a skunk sprays only when its life seems to be in danger. Some skunks can go for months or even years without spraying musk. That's fine with them. Skunks want to avoid trouble, and "play fair" with their many warnings.  A skunks’s stripes point to where the spray comes out. A 2011 study found that animal species that choose fight over flight when faced with a predator often have markings that draw attention to their best weapon. So while a badger has stripes on his face to highlight his sharp teeth, skunks’ stripes are perfectly positioned to highlight their ability to spray potential threats. By http://www.birdphotos.com via Wikimedia Commons  Larry Pringle has written many animal books, among them The Secret Life of the Red Fox. His The Secret Life of the Skunk was published by Boyds Mills Press in 2019. It is about spring and summer in the lives of a mother striped skunk and her kits.  When I take a big bite into a hamburger, I am taking part in a food chain. When energy moves from one living organism (hamburger) to the next (me), scientists call this path or chain the Food Chain. Every living thing needs food. Food provides energy for plants and animals to live. Food chains begin with plants using sunlight, water and nutrients to make energy in a process called photosynthesis. There are lots of different kinds of food chains— some simple, some complex. An example of a simple food chain is when a rabbit eats grass and then a fox eats the rabbit. I think food chains are so interesting, I’ve written some poems about them. A Shark is the Sun Shark eats tuna, Tuna eats mackerel, Mackerel eats sardine, Sardine eats zooplankton, Zooplankton eats phytoplankton, Phytoplankton eats sun. So...shark eats sun. In every food chain there are producers, consumers and decomposers. Plants make their own food so they are producers. Animals are consumers because they consume plants or animals. Decomposers have the final say as they break down and decompose plants or animals and release nutrients back to the earth. Animals can be herbivores (plant eater), carnivores (meat eater) or omnivores (plant and meat eater). What are you? Why Can’t I Be On The Top? I don’t like the bottom, I want to be at the top. I’m tired of being crushed and stomped and chewed into slop. Why can’t I be the tiger with claws as sharp as shears, With a roar as loud as thunder To threaten trembling ears? Who designed this food chain? Is there a chance I can opt out? At least I’m not a plankton Floating all about. I hope you are happy with your place in the food chain. If not, you might want to sing along with the Food Chain Blues. Food Chain Blues Mama said be careful, It’s a risky world outside, Dangers lurking everywhere, Hardly a place to hide. She said some of us get eaten, And some of us survive. Count yourself quite lucky, If you make it out alive. We’re stuck in this cruel cycle, Nature’s red teeth and claws. You wanna do your best, To stay clear of someone’s jaws. I got the food chain blues I got the food chain blues Someone’s gonna eat me. I got the food chain blues!  For more of Steve's poems about creatures check out Ocean Soup. It even has its own web page here. Steve Swinburne is a member of iNK's Authors on Call and is available for classroom programs through Field Trip Zoom, a terrific technology that requires only a computer, wifi, and a webcam. Click here to find out more.  Dr. Percy Julian was my neighbor in Oak Park, Illinois. I didn’t know the family who lived in the pretty home surrounded by an iron fence. But I heard the story, that the house was firebombed after they had bought it back in 1951. The Julian's were African-Americans coming to a white community. Later I learned more. Dr. Julian was someone who didn’t take no for an answer. He grew up in the segregated South going to black-only schools. He hoped to study plant chemistry, but no southern college would accept a Negro, so he moved on. He went to DePauw University in Indiana and helped pay tuition by waiting tables at a white fraternity. He graduated at the top of his class in 1920 and wanted to get his doctorate at Harvard. Harvard refused, because that would mean Julian could teach whites—and that was not allowed. Julian moved on. He went to Austria to earn his doctorate, and in that lab he studied chemicals in plants, especially beans. Many excellent medicines came from plant chemicals, but extracting them was often costly. Upon returning to DePauw to teach, Julian was able to synthesize a plant chemical called physostigmine. His discovery produced inexpensive medicine for patients with glaucoma, an eye disease causing blindness. But the Great Depression fell across America, and DePauw ran out of money to fund his research. Julian moved on. A Chicago paint company hired Julian as the first African-American to head a research lab in American industry. Julian had to travel for his work, and motels refused him a bed. One year he slept in his car 32 times, sometimes in the dead of winter. Julian and his coworkers developed inks and paper coatings, dog food and a product called Aero-Foam to extinguish fires on aircraft carriers. His team discovered many uses for soybeans, at that time viewed as food for cows and pigs. Most important, they synthesized “Substance S” from soybeans. This synthetic drug replaced wildly-expensive cortisone. Julian’s landmark achievement offered relief to kids suffering from the painful and disfiguring disease rheumatoid arthritis. Percy Julian worked all his days, always moving on to make life better. He built his own research business, volunteered at church, played the piano, and loved his family. He became a quiet hero to many, including me. I’m writing a book about Dr. Julian, which I hope you’ll see in print. For now, visit this site.  Kerrie Hollihan has already written about one great scientist, Sir Isaac Newton. You can read more about this book here. Kerrie Hollihan is a member of iNK's Authors on Call and is available for classroom programs through Field Trip Zoom, a terrific technology that requires only a computer, wifi, and a webcam. Click here to find out more. |

Traffic for our summer Minutes are ticking up.. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed